[At top is the edited version of the interview published by S. L. Sanger in Working on the Bomb: An Oral History of WWII Hanford, Portland State University, 1995.

For the full transcript that matches the audio of the interview, please scroll down.]

Book version:

After I left Massachusetts, I was stationed in Spokane and after that I went to Republic, up in the mines. In July, 1943, then, I was sent down here by the bishop when Hanford was just starting. Like he said at the time, I don’t know what they’re doing down there but you go down and take care of us.

On Holy Days during the week, I said Mass in a private home. There would be only a few women there. This project was only just starting, so there was no grass, and there was a lot of dirt and dust. When I finished saying Mass, I had brought a vacuum cleaner from Kennewick, I would vacuum the floor.

I went to Hanford. I was trying to find a church up there, at the construction camp. I have to back up a little. We started at White Bluffs. There was a church at White Bluffs, it was a Catholic church, an old dance hall originally, evidently. There was a ticket window in front. On my way driving up there, I would pick up the workers who were walking from Hanford to White Bluffs to go to church.

After that, they gave us a tent, in Hanford. A small tent, maybe a hundred feet long and just so wide. They put a confessional for us in there, a closet actually. The tent roof leaked. I said Mass there one Sunday when it was pouring rain. No lights. I used to light two candles on the altar so the people could know where the aisle was. That seated about a hundred at the most. One Sunday it rained and my housekeeper was there with her mother, and they had to sit between the puddles on the seats. I was giving communion and water was coming down on my bald spot and running right down my face.

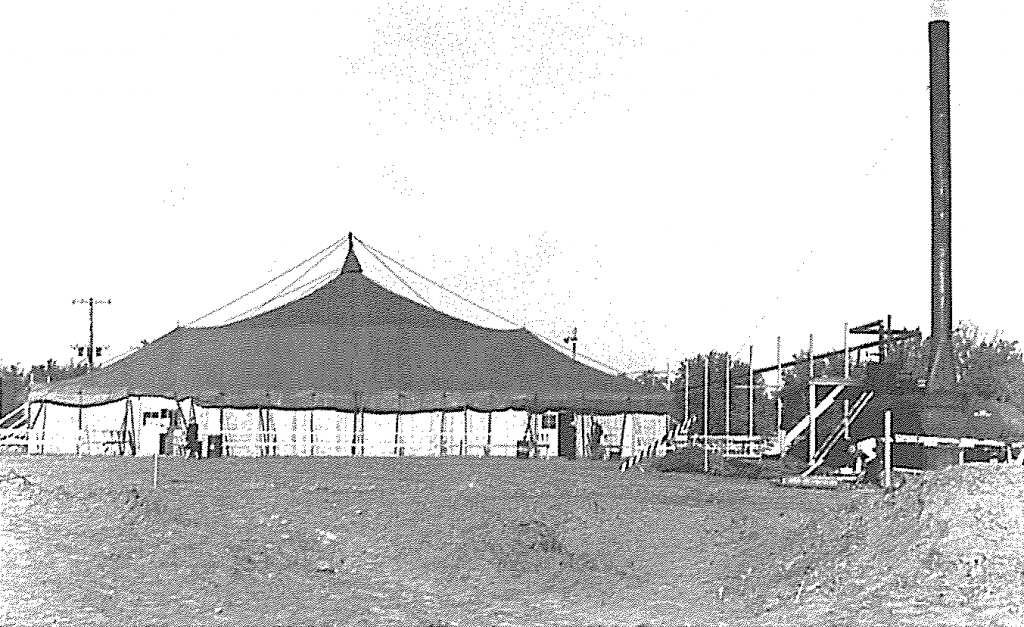

That tent was absolutely inadequate. That’s when they told me I could use the circus tent. It was already up, it was a big one, a regular three-ring circus tent. It was so big you couldn’t see the people sitting in the back. It was a movie theater during the week.

They gave me a room at the front, with a live steam pipe running through it. The room had two doors, one going into the theater and one to the outside. No windows. I would hear confessions on Saturday night and there would be two lines, everything had a line out there, one line going into the theater and the other line going to confession. The sound box was right in back of my chair and I would be giving instructions or hearing confessions, and I could hear the movie sound. Sweet music, sometimes machine guns.

Before the circus tent, I would give instructions in my car in front of Mess Hall No. 1. I would park my car in front and after they would finish dinner a couple who wanted to get married would come and I would give them instructions in my car. The windows would fog up, it was cold weather then.

The altar for the circus tent came from a church in Hanford, the town. It was one of those plaster altars, very decorative, and it made the tent look like a church. It was put on a platform, with wheels and everything. On Sundays it would be moved out of a storage room, and they made a little altar rail for me and a few kneeling benches. When I got the tent, I hadn’t really wanted it, I wanted a church, but it was a good thing. One of the officials, told me if you ever fill this tent, I’ll quit. Well, the next Easter, in ’44, I filled it.

Sometimes, I was so busy I wouldn’t eat breakfast until 4 in the after-noon. I had a private room in the barracks and would sleep there sometimes. You never knew who you were going to meet in the hallways, but they were always kind, very kind. Those people up there were extraordinarily kind.

We filled that tent Sunday after Sunday. The tent got ragged. One of the women at the service told me you know the people here are really obnoxious. They whistle all during Mass. What she heard was ripping canvas and the wind whistling through the guy wires.

There was a big accident, later in ‘44. I was on that. I had another priest living with me in Kennewick. I went home to Kennewick that day and the other priest came out white as a sheet, and said the Red Cross is trying to get ahold of you. The Red Cross wanted me to get out to the project because something had happened. I started out from Kennewick, and I got to George Washington Way, at the bridge.

There was a patrol car with two patrolmen. I said I’ve got to get through to Hanford, something has happened. They said we’ll take you and they started blowing their siren. You had to drive in the ditch then because they were building the street. The patrolmen started speeding, and from there on, that police car kept ahead of me in my little Chevrolet and I tried to keep up.

The speed limit was 35, I don‘t think in all my life I had gone over 40. My dad had an old car back home and when you got to 40 miles an hour it would vibrate. I tailed the patrolmen and we went by the 200 Area and they said we were going 80 miles an hour. All the guard stations waved us through. We got to Hanford and another police car took us to the hospital.

There was almost panic up there, with women from the trailer camp coming into the construction camp hospital to see if their husbands were hurt. The men had been working on a big tank and the tank fell. One fellow was on the operating table and I went in to him. Then they took me in to where the dead men were. They were black as coal, I thought they had been burnt. Peg, the head nurse, had gone through the pockets of these fellows and she found some Columbus medals or something on one of them, or two, so I took them first and anointed them. Then I went to the others.

When I left, I thanked the patrolmen for taking me up and you know what they told me? If our car had been up to snuff we would have got you up there in a hurry. I heard their car blew two tires the next day. I would have been killed because I was driving so close.

Yes, I was surprised at the bombs. I was in Spokane, in a store. I looked at the paper, and there was the story. That‘s when I found out. I don‘t recall my feelings then. But it was a terrible tragedy, and much worse than we knew. I object to nuclear weapons in war, but I don’t object to nuclear energy used for peaceful purposes.

I remember a man in Spokane asked me how I could work out here, he didn’t know how I could work in a place like this. I told him I am here because there are Catholics here.

Full Transcript:

S. L. Sanger: To interviewing Sweeney in Richland on June 12, 1986.

Sanger: Now why do you not tell me, because what we usually do is just get people to give us a narrative? That is the usually the easiest, and it is the smoothest as to when you came here and what you did and whatever you want to say.

Monsignor Sweeney: Okay. When I came here and lived in Kennewick—am I speaking loud enough?

Sanger: Sure. That is fine.

Sweeney: On July 3, I think it was, 1943. I had to live in Kennewick because I did not have a house here. And so I went from there—I did not do anything with Richland at the time. There were not enough people here. Well I did. Yes, I did. We used the Grange Hall, the former Grange Hall.

Sanger: In Richland.

Sweeney: Which is now the Lutheran Church, which did not look like that at all. It was only an old hall of dust and dirt. So we used that. Before using that, they let us use the school that was down the south end of town. There was a high school there.

Sanger: How many people were here then?

Sweeney: Oh, I would not know.

Sanger: You came out here as a young priest?

Sweeney: Yeah, young priest.

Sanger: Just to take over a parish, is that it?

Sweeney: Well no, I was stationed in Spokane for a year and a half. From Spokane, I went to Republic up in the mines for three years.

Sanger: Yeah.

Sweeney: Then I was sent down here by the bishop when it was just starting. And like he said at the time, he said, “I do not know what they are doing down there.”

But he says, “You go down and take care of it.” So I moved to Kennewick. The Kennewick church had about—on Sundays, we had about seventy people. That is pretty small. The Republic was quite small.

Sanger: Yeah.

Sweeney: And so I had to start saying mass here. There were not enough people. I do not know how many people there were. So I went down to the housing office for DuPont and asked them if I could not find a place here that I could say mass. They finally let me use the school, the high school, which there is only one high school in Richland, on Sundays. So I came up there and started saying mass. Well, that did not fill their auditorium.

Well on weekdays, we have six holy days during the year. Well I had to say mass, but I could not say mass in the school. The school was being used as a school. And that is before they moved the office. I do not know how they were doing it. But anyway, they needed the building. I could not use the school.

So I said mass in a private home on a holy day. There would be only a few women there and just a little story on the side. This thing was only just starting. So there was no grass. And it was amusing in a way. At least I think it is. I would say mass in their house, and they did not even have a vacuum cleaner in their house—a young married couple. So when I finished saying mass, I would bring a vacuum cleaner from Kennewick. I would vacuum the floor. So that just shows you how we are pioneering in a way.

So I said mass there that way. Then I went to Hanford. I was trying to find a place up there to say mass. I was trying to get a church up there.

Sanger: At the camp?

Sweeney: At the camp. So they called a meeting of the different denominations. There was a United Protestant—that took in seventeen different religions. They had started here. They used the Methodist church here, as a matter of fact.

Sweeney: They used the Methodist church because there was a Methodist church in town. And they let me use the Grange Hall on Sundays. Weekdays—I could use it then. When I got the Grange Hall, I could do that during weekdays as well.

Sanger: Is that in Hanford?

Sweeney: No, it is right here.

Sanger: Oh here, okay.

Sweeney: Near the end of the street.

Sanger: Yeah, right.

Sweeney: It is the church that is made in an odd shape in a way—of course our own is right now. But in those days, they did not have a church then. So there was a Lutheran minister up there. And a Protestant minister, one of the officials of the United Protestant Church from Seattle, myself, and a few people from DuPont. I asked them for a church up there as well.

Sanger: At the camp?

Sweeney: Yeah. Now at the camp, there was a church in Hanford. They were using that up there. I figured if they had a church that I could have a church or something. I was refused

Sanger: Which church was that at Hanford? Which denomination was using it?

Sweeney: I do not know. It was either Lutheran – oh, I think several were using it.

Sanger: Oh, several.

Sweeney: Anybody who wanted to use it, but I did not want to use it because I did not have the room. They did not ask me if I wanted to use it anyway. I was looking for a church of our own. They told me that they were not building any more churches. They were not going to build any churches. However, Richland, they were building us a church—two churches. There were two churches. United Protestant Church was built by the government, and ours was built by the government.

Now, the United Protestant had seventeen different religions under their roof. That was ministered by the Methodist. We had ours alone. So they built us a church, which seated 613 people. That is a government figure. So they could put in 600. On a midnight mass, I had over one thousand.

Sanger: Oh, you did.

Sweeney: Hanging from the chandeliers.

Sanger: This is by when?

Sweeney: By Christmas.

Sanger: Of ’43?

Sweeney: No, ’44. The church was finished on Christmas. Both churches were finished at the same time. The floors were hardly dry. And that was in ‘44. Then we opened the church. So then we got out of the Grange Hall, naturally. But at Hanford, we used that church until just five years ago.

Sanger: Oh, you did.

Sweeney: Then we built a new one, one million dollar church.

Sanger: Where is the old one? Gone?

Sweeney: Oh, they just used a bulldozer on it.

Sanger: Oh, it was up this way?

Sweeney: It was right up here at this other end of this lot.

Sanger: Oh, I see.

Sweeney: Where the church is, our present church, the other church was. So they knocked the church down.

Sanger: Oh, I see.

Sweeney: They took out whatever they wanted. We took out whatever we wanted and took our organ out. We had to buy all of those things ourselves. The government did not supply the organ, the alter, or any of the things or fixtures for our Catholic church. But they put the pews in and the kneelers. We had to supply the rest. So we opened on Christmas. That was the day of Christmas. It must have been ’44. And we said mass until just about five years ago there.

It was too small. But it was big enough to seat 613 people and at the midnight mass it packed over a thousand. Well in Hanford, anyway, getting back to that meeting, they did not refuse blatantly but they just said they were not building any. That was the refusal.

There was a church at White Bluffs. It was a Catholic church. It was an old dance hall, evidently. They had a ticket window in front of the place. I would go from Kennewick up there. I would pick up the workers walking from Hanford to White Bluffs. Do you know the area?

Sanger: Yeah, yeah.

Sweeney: There are only a few miles there. But they would walk. So as I came along, I would pick up whoever I could pick up.

Sanger: They were headed for the church?

Sweeney: They were headed for the church.

Sanger: In White Bluffs.

Sweeney: So we settled in White Bluffs. Well that was far too small. So they built us a tent in Hanford, the small town. This was oh, maybe one hundred feet long and just so wide. But they put a confessional for us in there, which was a closet actually. The tent roof leaked. I said mass there one Sunday when it was pouring rain out and no lights. And I used to light two candles on the alter so that people could find out where the aisle was.

And that seated about one hundred at the most, I think one hundred. It would be quite a figure. So one Sunday it rained. I know my housekeeper was there with her mother. They had to sit between the puddles—I mean puddles on the seats. I was giving communion, and the water was coming down on my bald spot and running right down my face during communion time. You can publish that if you want, but you do not need to. But anyway, so that was absolutely inadequate. So that is when they had that meeting. That is how the meeting came about.

Sanger: This would have been about when, the meeting?

Sweeney: Oh, maybe in ’43.

Sanger: Sometime in ’43?

Sweeney: Yeah, late.

Sanger: Later maybe.

Sweeney: Later, but see I came here in July. I would say that this would have happened maybe in October.

Sanger: Oh, okay.

Sweeney: October of ’43.

Sanger: But the tent had come before—

Sweeney: That is the small tent.

Sanger: Okay.

Sweeney: Alright, then this meeting came. That is when they told us that they had the circus tent up. It was a big one. I could not recognize the people out in the back of it.

Sanger: Oh.

Sweeney: That was used as their theater. They would take and use it as a theater all week long. But when they put the tent up, they put me a room. They gave me a room at the front with a live steam pipe running through it. There were two doors, one going into the theater, one going to the outside, but no windows or anything. So I held my meetings and whatever I had to do during the week in there. And I would hear confessions on Saturday night. And there would be two lines. Everything had a line up there. One line going into the theatre and the other line going to confession.

Sanger: Oh, on Saturdays.

Sweeney: Yeah, Saturday nights.

Sanger: So would you have some sort of a stall inside your office?

Sweeney: Yeah, it had a stall already. It was at the end of the tent. I could open the door and look out on the people in the hole watching the movie.

And the sound box was right in back of my chair. I would be giving someone instructions on something and I could hear the sound and sweet music. Then you would hear machine guns running. I was really curious to see what was going on, but I never saw a picture up there. I was always too busy. I was really busy. I was going up there sometimes as many times as three times a day from Kennewick. Then I would give instructions in my car in front of Mess Hall Number One, for marriage. I do not know what faith you are.

Sanger: Methodist.

Sweeney: Methodist, well you were probably given instructions. I did not know where they did that or how. They had a church. So I would park my car out in front of Mess Hall Number One. After they finished dinner, they would come out. The couple would sit in the back seat of my car. I would sit in the front. I would give them instructions from the car. Now you can see what time of the year. My windows would all fog up. We were getting pretty close.

Sanger: And this is for somebody who is going to get married you mean?

Sweeney: Yeah, getting married. So then, I accepted the big tent. The fellow told me then that it would be ours for Sundays. So there were no pictures shown on Sunday afternoon or Sunday morning. We were not saying evening masses then. I would go up on Tuesdays, and I would give whatever I had to give – instructions. They had an altar. They took the alter from Hanford.

That church at Hanford—I do not know when it was used last. But the priest used to go up there from Kennewick once in a while. Now how often, I have no record at all of how often he went there. But there were Catholics living up there before the project came in. They were still there.

I am still dipping back to that big tent. But I would go up there on Tuesday nights. I would eat up there in the mess hall. I had friends up there that always took me in the back door. If I had to pay, I paid whatever it was. I think sometimes I got in there free. I do not know. They just took me in. So I would give those instructions outside the tent.

Then finally, when I got the tent that is when I started. I was giving instructions in that tent in that office in the back. Now they had the equipment. That is what we were speaking about. They used an alter that was taken from some church some place. I do not know where. See those things that I do not know at all that had probably been there for years. And it was one of those plaster alters. Do you know what a plaster alter is?

Sanger: No.

Sweeney: It was very decorative. And it made it look like a church. It was all reinforced plaster. And they had that on wheels. They had a whole platform. They made a platform for it with the wheels and everything like you would move a piano. And they moved it out of a back storage room and put that out there, made a little alter rail for me. The people would sit out and had a few kneeling benches.

But the thing got big. And as a matter of fact, when I got the tent, it is not what I wanted. I had wanted a church. But it is a good thing that I got the tent. One of the officials, not from here told me, “If you ever fill this tent, I will quit.”

Well the next Easter—that must have been ’45—I filled it. I had gone up there in the morning and heard confessions for two hours. Came back to Kennewick, and I was not living here at all. And I went up there at night. I started at 6:30 in the evening. We went until 12:45 in the morning without a stop. I would walk about every hour or so. It was a tremendous line. And I would not watch the line. I kept my eyes off them. Usually, you do not want to face people. I would go out. I made ice water. It was on the poles—they had tied barrels of ice water on all the poles of the tent, and salt pills next to it because of the climate.

And so I went to 12:45 in the morning. As a matter of fact, I was leaving at 12:30. And I got a call at the hospital. I knew my way around. So I called the priest in Pasco and asked him to bring up the Blessed Sacrament so I could give it at the sick call. When he got there, he heard the last fifteen minutes of those confessions while I went to the hospital, and when we came out—there were two roads at Hanford. It went to White Bluffs and it went into Hanford. Right there, I stopped. I made a California stop. Do you know what I mean?

Sanger: A moving stop?

Sweeney: Well you stop, but you just stop and go.

Sanger: Yeah.

Sweeney: A police car just blew its siren watching for the night fellows, the fellows on Saturday night. This was Saturday night. And I was dead tired. Boy, I had been going since early morning. So they came out. I said, “Sorry fellows. This has been an awful long day,” or whatever it was.

They said, “We know.” What had happened on the sick call, it all went through the same radio. So the police or the patrol called Kennewick, whoever, the hospital called Kennewick trying to find me. When they could not find me there, that meant that I was on the project. That is the way it went. I could not go anywhere. So he says, “We heard.” So they said “Okay, watch out for the road.” Then I came in.

We filled that tent Sunday after Sunday. Then the tent got ragged. As a matter of fact, one women found some of the people after the masses, or they would stop and talk with me. I would not eat breakfast. One Sunday, I ate breakfast. We could not eat in those days from midnight until after mass. I could not get anything to eat up there. It was too late. And when I ate breakfast, it was 3:45 in the afternoon in Kennewick. So this thing, if you want to put it, it is all right. I am just giving you this thing’s history. So anyway, we go through that Easter and kept on going. And the crowd held up.

Sanger: Could that have been ’44?

Sweeney: It was ’44.

Sanger: Yeah, okay. That is when the big Easter crowd was.

Sweeney: Oh, yeah.

Sanger: Yeah.

Sweeney: And then it got smaller because the other Sundays—it was not Easter. So like at any other church, the crowds got a little smaller.

Sanger: Do you have any idea how many people crammed into the tent?

Sweeney: Possibly 1,500, at least.

Sanger: Because it was a big circus tent?

Sweeney: It was a big one.

Sanger: Great big.

Sweeney: You could not see the people at the other end. Oh, it was a regular big one.

Sanger: Wonder where they got that at.

Sweeney: It was a three-ring circus tent.

Sanger: That must have been quite a site.

Sweeney: It was. I have got the picture of it some place.

Sanger: Did you take it?

Sweeney: No, no, no. Rob took it.

Sanger: Oh, did he?

Sweeney: I got permission from the—

Sanger: Alright, the woman and the comment about the whistling?

Sweeney: Oh yeah, well that there, she just said that at mass they would stay up in the front because they had no place to go. And they would talk with me. So she says the people are really just obnoxious. They are whistling all during mass. All it was, was the wind blowing through the guide wires and the canvas was ripping. Now they had no more movies in there. So they had to take down the tent and put up the auditorium. Now you probably heard the story on the auditorium.

Sanger: The fast work?

Sweeney: It was all done in one week or something like fifteen days, or something like that. Now they had offered me one of the mess halls. See there were five—was it five or seven mess halls in there?

Sanger: Yeah, there were seven or eight, I think.

Sweeney: Seven, and they were not all used. They wanted to put me in one of those. I did not want to go because it could not handle the crowd. So they wanted to put me into the theatre. And matter of fact, the bishop came up

Sweeney: they put the auditorium up. They built the auditorium so that I had quarters.

Sanger: Oh, you did?

Sweeney: Oh, yeah. On the back of that auditorium, which was a wonder of wonders, I had the most beautiful floor in that place. I saw her a year later, and I will tell you about that later. But I had rooms out in the back. First of all, the room was big enough for me to have, on Tuesday nights—I kept on my Tuesday night meetings. The choir would practice up there. I gave instructions up there.

Then I would have some devotions, some kind of a devotion forum. We could not have those in the regular church. So we had devotions there. When that was finished, we played bingo. The prizes were not money, they were religious articles just to keep the people. They would serve donuts and coffee. I had a kitchen, refrigerator and everything, in that back room.

So we used the auditorium and it was very good, very, very good. And of course, on Tuesday nights when I would go up there, they had other things going on in that big auditorium. I could not have anything in there. I came in one night, and they had opened my office. Here I had a girl in there on the piano. She was playing. She said “I used to be in really good bands.” Then she was thumping her music on keys and timing. Here, I needed it for my work. So I had to tell them we will have to take and cut this short and let me get on my work.

So finally, I decided to go down. I had a little room in back of that, I used to call it the caboose. I would hear confessions in there. And I used to have union meetings in there during the week, and cigarette butts and everything else were around. Well, there are a lot of stories that would not fit in here. I mean I do not think anything at least—sick calls and things like that, funny thing that happened. The big thing that had happened up there, there was a big accident.

Sanger: Well that is what I was going to ask you about. Why do you not talk about that?

Sweeney: I was on that accident. I was here, right in Richland. I was not living here yet. I had another priest living with me in Kennewick in a little house. Red Cross was trying to get a hold of me to get me out on the project for this thing that had happened.

It is funny, as a matter of fact. I could not speed between here and Kennewick because the state patrol was watching this place. They had their own idea. I used to go out. One Sunday—I would go out there at 11:30 ordinarily. In Richland at nine o’clock and Kennewick at seven o’clock, but once a month, I would reverse the order. And I would sleep up there. I would sleep in one of the barracks. I had a private room in the barracks.

Sanger: Oh, you did?

Sweeney: The other priest would use it one week. I would use it the next week. The only trouble is they changed sheets during the week. And I was never there when I could change sheets. So we had to switch this, change it around at night. And you never know who you are going to meet in the hallways. But they were always kind, very kind. Those people up there, I mean, were extraordinarily kind.

I would go into the mess hall to eat at night once in a while on Tuesday nights. And you would get in there. You would have to get in and find an empty space between. I had benches down there. They gave us some of the benches afterwards to hold up our air conditioners on the old church.

Sanger: Oh, is that right?

Sweeney: I would go in there. As long as I held a platter up whenever the platter was empty, I was safe. And they would not sit down. They stood right next to me, and they would eat. So I was uncomfortable. I got a sick call one night and – well, we better get down to that accident.

Sanger: Oh yeah.

Sweeney: So I started off in Kennewick. I was nervous, naturally. I got to George Washington Way, down at the bridge. And they were just putting in George Washington Way. See how long ago it was. And I stopped the first car. I did not know what had happened. I was teaching here in the morning. I went from here with the kids, went down to Kennewick, and the priest came out as white as a sheet. He said the Red Cross is trying to get a hold of you. Everybody is trying to get a hold of you. So I turned right around and came up.

So when I got to the bridge, there was a motorcycle policeman there. I asked him if he would lead me to headquarters. Headquarters was down—well where the travel agency is down there.

Sanger: Oh, yeah.

Sweeney: Next to the Ridley Inn. It was there.

Sanger: I know where that is, yeah.

Sweeney: And the offer said to me, he said, “I cannot take you through without permission.”

So I said, “Okay.” So I let him go.

The next street, there was a patrol car with two patrolmen in it. I did not know them. They knew me. One of them knew me, I think. I said, “I have got to get through to Hanford. Something has happened and I do not know what has happened.”

They said, “We will take you through.” They started down blowing their sirens. Washington Way, you could not go on it. You had to go on a ditch on the side because they were still building there.

We came in front of headquarters down there. All the officers are out in the front of the place looking down the street for us coming along, because the accident was coming from the Kennewick side. It wasn’t coming from Hanford. Then I really got scared because I had figured that I had asked for something that I had no right to. But the two patrolman were in the car, and I noticed them bring up the phone. One of them took the phone and talked to headquarters. I say this is when I am going to get canned, if you want to use that expression. Instead of that, they started speeding. And I still did not know what had happened because they gave him the okay to get through.

But from there on, that police car took and kept ahead of me. And I tried to keep up with the police car. And I was young then. The speed limit was thirty-five miles an hour. And I do not think in my life I had ever gone over forty. My dad had an old car back home; when he would go to forty miles an hour, it would vibrate.

Well I tailed that fellow out there. We went by 200 Area and they said we are going eighty miles an hour. I had never even ridden that fast. So we went up and the guard stations were just waiving us through. We got to Hanford and another police car was waiting for us. The two police cars took me down to the hospital because the accident had happened sometime before that. It was almost panic up there with the people from the trailer camp—it was the biggest one in the world. The people were coming in to see if their husbands were caught in it.

Sanger: And that was where the accident happened.

Sweeney: Out in the area, I do not know just where it happened. I did not go to the accident scene.

Sanger: At the hospital?

Sweeney: I was at the hospital. They were chipping on a big tank, and the tank fell.

Sanger: Yeah, do you know how many people were killed? Do you recall?

Sweeney: I think five.

Sanger: Yeah, I have heard that—five to seven.

Sweeney: Five, I do not think seven. There was more than that. One fellow fell between the beams and was not injured. And another fellow fell between and was hurt. They had him on the operating table. I went in to him, then. Then they took me in to the dead ones. They were black as coal. I still do not know—Peg—I cannot think of what her name is now, but the head nurse, they went through the pockets of these fellows. I thought they had got burned. See I still did not know what had happened.

So she found Knights of Columbus medals or something on one of them or two. So I took them first and anointed them conditionally. When we are in doubt, we just go ahead and anoint them conditionally. And I went through the others. And I went into the operating room to the one that was still alive and who lived.

Sanger: Yeah, I think it was the 200 Area where they were working on some big tanks.

Sweeney: So I never knew just where it was. On the way back, there were the two patrolman at one of the stations. They were talking with the guards there. I went through, and I thanked them for taking me up. And you know what they told me? “If our car would have been up to snuff, we would have got you up there in a hurry.”

Sweeney: Now the other part of the story, I cannot verify. But I hear that that same cop blew two tires the next day. I would have got killed because I was so close to them.

Sanger: Yeah, were you driving or was someone else driving?

Sweeney: No, I was driving.

Sanger: You were driving. Was it your car or someone else’s?

Sweeney: Yeah, my car, a little Chevrolet. And I had never driven that in my life. I had never even ridden in a car that would go that fast. I was shaky. So we got up there and got back. But there stood these two gaurds. One of them, I met him several times after this. He used to tease me about that trip up there.

Sanger: Were there any other major accidents like that in your experience?

Sweeney: No.

Sanger: That one would have been in ’44 you suppose, or later?

Sweeney: 1944.

Sanger: Yeah, because I was talking to a man who was one of the supervisors with the patrol and he was talking about that accident.

Sweeney: They had an accident before. See, those days, everything was so hush-hush that you heard nothing. And I asked no questions. We had one incident that happened. Boy I tell you, the military intelligence, I have got pictures. They are right in the volume of the dedication of the church. All the ushers were military intelligence.

Sanger: Oh, is that right.

Sweeney: Well now, what happened—that was not done on purpose. These fellows were placed from the Fordham and other Catholic schools. To get in, they had to have quite an education even before that. So when they came to church, their wives were not here. So they came to church, and they acted as our ushers. When we had the picture taken after the whole group, they [inaudible] with the military intelligence.

Sanger: Did you have any idea what was being made out there at all when it was going on at the project?

Sweeney: That, I will not say. Nobody everybody confided in me. I would not even ask. They were building a big, big chimney down the center of the town here. It was for the heating plant. I would not ask a question about what that thing was being built for.

Sanger: That was fairly normal, I suppose.

Sweeney: That was the best kept secret.

Sanger: Then I suppose the camp closed in February, did it not?

Sweeney: In February, I went up there for the last time to say mass in the back of that auditorium. There was only about fifteen or sixteen people.

Sanger: Oh, is that right? Down from 1,500 or so?

Sweeney: Down from 1,500. It was cold. They shut off all the utilities. Everything was shut down. As a matter of fact, that is where I got my housekeep. I asked her, I said “Does anybody know anybody that wants to be a housekeeper?”

This woman said, “Well my mother is coming down from Canada in Vancouver. And that would be a good job for her.” That is where I got my housekeeper. But a year later or more, I got a call. See I was also chaplain to the prison chapel—to the federal camp out here.

And I had to go out there on Mondays. I could not go on Sunday. We could not say that many masses. So I would go out on a Monday morning. I got a call from one of the men down here. He said, “There is something I want you to know.”

The alter that I used—see that was in the room. That was in that back room. And they had rolled it out, see. They moved all that stuff. They insisted. They said we can make it look like a church for people. They wanted to keep the people at Hanford.

Christmas, they would give us oranges and everything else for kids. And they would do everything they could for us to try to satisfy the people with things they wanted. Dupus Boomer—did you ever see the books on Dupus Boomer? That has nothing do with the Catholic Church though. The pamphlet, Dupus Boomer was a worker out there. And it was mostly on Richland. And it was all jokes. And it was one of the best things. I will not let anybody have those.

Sanger: Oh, is that right?

Sweeney: Yeah, and Dupus—all kinds of things would happen to him. And it’s things that we knew of the wind and all that kind of stuff. They would make jokes out of it and have cartoons and some little newspaper that they were putting out.

Sanger: Is that the Sage Sentinel? Is that it?

Sweeney: I do not know what it was.

Sanger: That is where that appeared.

Sweeney: Yeah, and so they made it into book form and pamphlet form. I think there are two of them. I have both of them. And that gives you quite idea of what was going on out here. Nothing that they were doing.

Sanger: Do you suppose they have them over at the library?

Sweeney: I do not know.

Sanger: What was it? How do you spell that?

Sweeney: Dupus, D-U-P-U-S, Boomer, B-O-O-M-E-R [misspoke], something like that.

Sanger: Anyway, what is that? Is that just the name of the character?

Sweeney: The name of the character.

Sanger: Dupus Boomer?

Sweeney: Yeah.

Sanger: Anyway, so then in February?

Sweeney: Sure, the place closed. But a year later, that fellow called me. He told me, he says “That alter that you had up there has been desecrated.”

So he said, “Do you want to come up with me?”

I went up there with him. And see I was carrying my badge—I always had that badge. We got up there and I saw what happened. They used a sledgehammer on the front of it. And the insignia that was on the front of the thing was all bashed in.

He said, “What are we going to do with it?”

So I said, “I will tell you. Dig a hole and bury it. Just take the whole thing. You have to use a crane and just put it in there.” So it is buried up there some place in Hanford.

Sanger: And the building was still there. They had not demolished that yet at that time?

Sweeney: Yes, but you ought to see the floor in that auditorium. It was a mess. They sold it to a company. From what I hear, they sold it to a company in Yakima.

Sanger: That is right?

Sweeney: For fruit storage or something.

Sanger: Oh, they did?

Sweeney: But the floor, that beautiful floor. They had the best basketball teams and everything else they could get up there, dances, and everything else. And to see that floor—it was a heartbreak.

Sanger: It was beautiful before?

Sweeney: They did a beautiful job on that building.

Sanger: In what, a week or ten days or so?

Sweeney: Yeah.

Sanger: Isn’t that amazing? Well by then you what, you had your church down here then?

Sweeney: I had the church here. We came in on Christmas—I think of ’45. And I have had it ever since, until they destroyed it four or five years ago.

Sanger: When the bombs were announced, were you surprised at that or not? Do you recall?

Sweeney: Yes, because I did not know what it was. I mean, I could not tell you anything about it. I was in Spokane. I was in the store. I had gone up for the day. I could never get away. I would go for a day and come back. The other priest would cover for me down there.

I looked at the paper in Spokane and there was the whole thing that Truman had given permission to [bomb]. That is when I found out. And that is when people called their husbands out in the area to tell them what they were doing.

Sanger: Oh, is that right?

Sweeney: Now you know as well as I do, the engineers, chemists, or physicists knew what was going on.

Sanger: Yeah, they knew what they were doing.

Sweeney: They knew what they were doing.

Sanger: But a lot of people did not.

Sweeney: Oh, they did not know it. No, they did not know it. My janitor worked in the 300 Area as a carpenter. He used to stay at the church when they first built the church, to fire the boilers to get used to the system and all that. He would fall asleep over there after doing his work, and he got curious. He started going through encyclopedias. He came up with mercury. And so what happened? One of his fellow workers who did not like him reported him to the military intelligence.

Sanger: As being someone who was too curious?

Sweeney: He had some knowledge or whatever it was. So they went down on him. And they forbid him to talk to anybody. He had to talk to somebody, so he talked to me. He told me about what had happened. So when he went one day into military intelligence—and the fellows there, I knew them all or practically all, there were not that many—they went back to him. They said, “Did you tell anybody?”

He says, “Yes, I told Father Sweeney.”

They said, “What did you tell him for?”

He said, “I had to talk to somebody.” He was way off on the whole business. But they kept him right on the job here. Oh, they would not let him go. That is a story that very few people know, very few.

Sanger: I have heard a couple of things. Not that one, but I have heard a couple of things like that where somebody would decide that he knew what was being made out there and they would immediately crack down on them, especially if you told anybody.

Sweeney: Oh, I would never talk about the projects or anything.

Sanger: Well so then things tapered off, I mean as far as the people went, really pretty quickly after the camp was closed?

Sweeney: Oh, yes.

Sanger: So then you say your church here opened about when, the one in Richland here?

Sweeney: Which one, the one the government built?

Sanger: Yeah, the one the government built.

Sweeney: Christmas 1945.

Sanger: Before I forget, you grew up in Worcester?

Sweeney: Oh, yeah.

Sanger: And then came here?

Sweeney: Came here in 1938.

Sanger: ’38, yeah, okay, before I forget that.