[At top is the edited version of the interview published by S. L. Sanger in Working on the Bomb: An Oral History of WWII Hanford, Portland State University, 1995.

For the full transcript that matches the audio of the interview, please scroll down.]

Book Version:

Bill: When I came here I was 27 or 28 years old, and I‘ve been here 42 years. My previous job was at Bridgeport, Connecticut, at a Remington plant, making ammunition, anything from .22 caliber up to 20 millimeter. I went into operations in the 300 Area, where we were canning the uranium for shipment to the 100 Areas. By then, it was June,’44, they were breaking their butt in the 300 Area to get enough uranium metal to charge these reactors. They had beaucoup trouble. I was kind of a flunky the first month. Then I went on the autoclaves. Each slug, let’s see, there were 240 slugs, placed in a series of baskets and put in the autoclaves and cooked for 24 hours, to see if there were any defects in the can.

I stayed at the 300 Area until Halloween night, ‘44. After the 300 Area, I went back to B as a “D” operator, the lowest level there is. I worked in the 115 Building, which provided the gas atmosphere for the reactor. It was helium. My job was kind of sitting around taking readings because it was fairly automatic. After you were an A operator, you did control room work, they called them pile operators.

Later, I was a pile operator, controlling the rods, taking readings, taking your turn at the control console. At the console, you keep the reactor at a certain level. It wasn‘t difficult but you couldn‘t go to sleep. You had a galvanometer in front of you, any minor movement of a control rod would move it. That measured the reactivity. You would look at it, and if the meter went to the left, you were losing power, so you would pull a rod. And if it went to the right, you would poke a little in. After you got up and leveled out the power, the reactor was pretty stable. Somebody watched the panel with the couple of thousand process tubes. Each tube had a light and if a light came on there was something wrong. That didn’t happen very often. If a light came on, it could be a malfunction of the gauge, maybe an indication of a fuel element rupture and the tube was blocking up. If the tube blocked up, the pressure would go up. If a fuel element ruptured, you would shut down the reactor and try to push that tube. If you couldn’t, you would call in maintenance. The training for reactor operation was on-the-job, there was no other way.

I didn’t have any idea what we were doing. It didn’t bother me. I had a job, it was a war effort. That‘s the way it was. Aw, people used to talk, saying we were making Kleenex or clothes pins. My wife and I and another couple were walking down a hill in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on a Sunday, going to the movies when we heard about the war being declared. That had more effect on me than hearing about the bombs. It was one of them things, you took it in your stride.

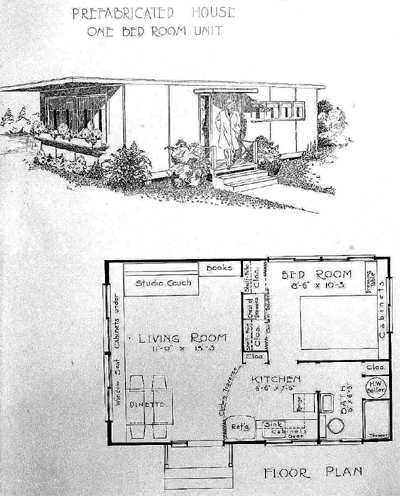

Louise: When we first came here, it was kind of wild. There was nothing here. The sand was knee-deep. We picked out our first house, a one-bedroom prefab. We rode the bus out from Pasco and came out what is Lee now and cut across a big sand dune, which is now a junior high school. We walked up that and came down and picked out our one-bedroom prefab. At the time it was half built. We were the only ones on that street who had two plum trees.

The city gave us the grass seed. Before that we had bulldozers running back and forth in front and back. We had the best lawn in the neighborhood. There was lots of irrigation water, we got it out of a ditch. Our little house had a little porch. You walked in the front door, and took a left. That was a combination living room and dining room. To the right, was the kitchen and off the kitchen was a bedroom, and a bathroom. Only it just had a shower, no bath. The rent was $27.50 a month, for everything. Heat, water, furniture. Our little house is still there.

Bill would work shift work and go to bed in the morning and leave the windows open. When he got up you could see his imprint in the bed. The sand wasn’t really a problem, though, because it was easy to pickup. We came from the East, and back there you had dirt, but you had greasy dirt. It would stick to everything and you had to scrub it. Here, all you had to do was get the sweeper and sweep it up. We had no humidity.

When I got to Pasco on the train from the East, it was terrible. If Bill hadn’t been there at the station to meet me, I’d have gone on someplace else, maybe California. The station was all the time crowded with men. The men never shaved, it was hard to get laundry done. Construction workers would wear their overalls until they couldn’t wear them anymore and then they would buy a new outfit. We had one friend that made a fortune doing laundry. She came from South Dakota and she happened to have a beatup second-hand Maytag.

We had a lot of fun in that one-bedroom prefab. Everybody was from all over the country and didn’t know anybody. So, you got acquainted real easy. The neighbors would come in for breakfast when Bill came home from the graveyard shift. They would come in at night when he was on the swing shift. We would have dessert together. There wasn’t any entertainment, so we would play cards. Out in the camp, they had a big dance hall, and we would go to those, and dance to big bands. We considered ourselves kind of like pioneers.

Full Version:

[Bill’s Interview]

S.L. Sanger: This is an interview with Bill Cease on the first of July, 1986, at his home in Richland.

You said that you came from Bridgeport. You worked for the Remington Plant there?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: That made ammunition?

Cease: Yes. They made .22s up to, I guess, the biggest we made was twenty millimeter.

Sanger: How long were you there?

Cease: Three years.

Sanger: Is that where you grew up?

Cease: No, I grew up in the coal mining area of Pennsylvania, near Scranton.

Sanger: Oh, you did. Then you would have been how old then, when you were working at Remington?

Cease: Let me see. I graduated in ‘31 and that was in 1941, so I was twenty-seven, twenty-eight, twenty-five, something like that.

Sanger: Were you married then?

Cease: Yeah. I got married in the Depression.

Sanger: How old are you now?

Cease: I will be seventy-four this week.

Sanger: Anyway, you told me once, you can tell me again—you were at Remington at Bridgeport and how did you happen to come out here?

Cease: It is not really complicated. This little town I grew up in, let’s see—you are acquainted with Cle Elum? It was a town probably the size of Cle Elum. We had neighbor and I used to run around with this fellow. His folks had money, and mine did not. He went to Penn State and he graduated as an architect, and he got a job with DuPont. We happened to be home in this little town.

Sanger: Which town was that?

Cease: Little town called Trucksville.

Sanger: Trucksville?

Cease: Uh-huh. It is about six miles out of Wilkes-Barre, kind of a bedroom community. He was visiting his sister, who lived next door to my folks. We got together one afternoon and he was telling me about this project. So when I went back to work I told my boss that I had heard about it and if he ever heard anything about it let me know, which he did.

Sanger: What did the guy, your buddy, tell you about it?

Cease: He just said that DuPont had a big job in the State of Washington. It was hush-hush job.

Sanger: What did he do for DuPont, do you remember?

Cease: He eventually wound up here.

Sanger: Oh, he did?

Cease: Yeah, for a short time. When he was, here he was—I think one thing a lot of people do not understand is that we had an excess of people that started, because we did not know what was going to happen. You did not, either. Nobody knew. It was either going to go or it was going to die. So they were well covered. At that time, they had a maintenance engineer on every shift, which later on we got some smarts and they were eliminated. Put to better use in other places, until they were not needed.

Sanger: Anyway, you went back then to Bridgeport after that conversation. Your boss eventually let you know?

Cease: He told me in early March or late February in 1944, there was a fellow down at the main office. He talked to me. There were four people from Bridgeport came here. That is all.

Sanger: Is that right? Why is that?

Cease: They had a lot of defense work. Bridgeport is a very industrial town. They just would not recruit people. They did not want them to recruit people.

Sanger: Because they needed everybody to get there. How did you happen to get away?

Cease: I do not know. I do not know.

Sanger: What were you doing there at Bridgeport?

Cease: Do you know anything about explosives?

Sanger: Well, not a lot, no.

Cease: Dynamite is a high explosive but primer mix, which goes into the primer which sends a projectile out is called initiating explosive. It was highly volatile, it set off just by static electricity. [00:09:00] I was in primer mixer.

Sanger: They were making ammunition?

Cease: Yeah, for the war.

Sanger: Is that a fairly high-risk job?

Cease: Not really, if you follow the safety instructions. It is just like any other. I never had any qualms about it, but you better follow the safety rules. For example, every time you went to your mix, each table had a bar on it and you grounded yourself to get rid of the static electricity. You made graph in every house to keep the humidity at seventy-five percent. The way you did that was by a steam jet, like a Cobra, steam or you could just wet everything down with a hose.

Sanger: That kept the static electricity down?

Cease: That kept the humidity up. It was an interesting job, I enjoyed it.

Sanger: Then you came out here? Did you train before you came to Hanford? What was the job here, then?

Cease: I had a choice of three jobs: carpenter, security patrol, or truck driver. I was more fortunate than a lot of people in the East in the Depression. I never lost a day’s work in the Depression. I did not make a lot of money. But I made enough, I saved money so Louise and I could get married. I did not want any more truck driving. I had had some carpenter experience because my dad was a master carpenter, but I did not think I could hack it, so I took the security patrol.

Sanger: You came out in what?

Cease: I drew my first day’s pay March 13, ‘44. I got here I guess on about maybe the eleventh or something like that.

Sanger: So you went to work as a patrolman for DuPont?

Cease: Uh-huh.

Sanger: On which area?

Cease: B, at the reactor.

Sanger: How far along was it then?

Cease: It was pretty well along. They were putting all the piping in the 115-Building and they were hauling in the blocks of graphite for the reactor. The graphite was not laid yet. They were putting the shielding on the near far side, and they referred to the blocks, they were about four by four by four.

Sanger: Yeah. So the concrete was up?

Cease: Oh yeah.

Sanger: Then what were your jobs as a patrolman?

Cease: I worked the badge house during shift change.

Sanger: And that is where you check people, coming and going?

Cease: Yeah, check the badges in and out.

Sanger: Out as well as in?

Cease: Yeah, oh yeah. It was a pretty soft job. All I had to do was wander all over the 105-Building and look for what I considered fire hazards or trash laying around and a welder working close by, and this kind of thing.

Sanger: Was that during the daytime, or any number of times?

Cease: Well, I worked shift work.

Sanger: Did you ever find anything?

Cease: No.

Sanger: Was it fairly high safety standards?

Cease: Oh yes, you bet.

Sanger: There were probably hundreds of men swarming over the place.

Cease: Uh-huh. We just lost a fellow here about a year and a half ago, two years ago, Johnny [John] Manophoulos, some people called him Monopolis [13:46]. He was a Greek. It was kind of interesting, he was a runner. He would run from the engineers, who had a building. They would take a piece of eight and a half by eleven and a half paper. That was a piece of print and you are a fitter and you are working in one part, when you got to the edge, you had to have another piece. So he would take that one back and being in another one.

Sanger: Then you stayed on that job for how long?

Cease: Three months.

Sanger: And then what?

Cease: I got notified to report to camp [inaudible] in Hanford, which was the headquarters. I never was able to find out, but I think it took just about that length of the time for my folder to get from Bridgeport to Hanford. I do not know.

Sanger: About your experience?

Cease: Yeah. Then I went into Operations. They moved into the 300 Area. There we were canning the uranium for shipment to the 100 Area.

Sanger: So you would have gone there in ‘44?

Cease: June.

Sanger: June. And by then, what was going on in the 300 Area?

Cease: They were breaking their butt to get enough metal to charge these reactors. They were in beaucoup trouble.

Sanger: That is when they were having trouble with the canning technique? What was your job there?

Cease: Kind of a flunky for about the first month, and then I went on what we called the autoclaves. Each slug, let’s see, there were 240 slugs, I think. I guess slugs were placed in the series of baskets and were put in an autoclave and cooked for twenty-four hours.

Sanger: What was the purpose of that?

Cease: To see if there were any defects in the can. Of there was, then it would show up. You would take them out and inspect them.

Sanger: I see. Very hot, you mean?

Cease: Oh, yeah. It was under steam pressure.

Sanger: These were the actual slugs?

Cease: Uh-huh.

Sanger: They were about six inches long?

Cease: They were about nine inches. Just a hair over an inch in diameter.

Sanger: Oh, but nine by one inch in diameter?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: By that stage, were a lot of them faulty?

Cease: No. They had gotten their act together and they were doing a pretty good job.

Sanger: That would have been by late July?

Cease: Well, let’s see. I went down there in June, July, August, September, October—I left there on Halloween night, in October.

Sanger: So the reactor was loaded by the end of September?

Cease: Yes. When I went out there, they were operating it.

Sanger: Then you stayed at the 300 Area until when?

Cease: Halloween night.

Sanger: In ‘44?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: Did you stay at the autoclave [00:18:00] job?

Cease: Uh-huh.

Sanger: Did you see any of the uranium extruding operation ever?

Cease: Well, in those days, it was not extruding.

Sanger: Oh, it was not?

Cease: No.

Sanger: How did they do it?

Cease: It came in a big bar, in a big box, even longer than this swing. They were shipped in in bar, and then they had a [inaudible] lathe where they machined it.

Sanger: Just down to the slug size? So it would have been, what do you think about the box, about eight feet?

Cease: They were at least eight feet long and a couple of feet squared.

Sanger: That was just pure uranium, right?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: It must have been really heavy.

Cease: Everything was handled by the forklift.

Sanger: I wonder, do you happen to know where that came from? Because nobody has remembered where the uranium actually came from.

Cease: I know where the finished slugs come from, so there is no reason to believe that the rods did not come from the same place.

Sanger: Where is that?

Cease: Fernald, Ohio.

Sanger: And that is where it was put in the billet form?

Cease: Later on, they just received the raw slug, without the can or anything.

Sanger: Oh, they did?

Cease: If you think about it a little bit, this is an improvement. In other words, you have all the shavings from the machinery. Okay, why not put them back in the process again?

Sanger: Yeah. At least you could do with the source. What did happen to the shavings?

Cease: They were canned.

Sanger: Sent back?

Cease: Yeah. They were in buckets with an airtight lid, just like a paint bucket with the things around it.

Sanger: Well, then when you went out to the 100 Area, right?

Cease: I went back to B.

Sanger: As what?

Cease: A D operator.

Sanger: Which is what?

Cease: The lowest level operator there is.

Sanger: At the reactor itself?

Cease: Uh-huh.

Sanger: What did you do there?

Cease: I worked in the 115-Building. You are familiar with the gas atmosphere and the reactor?

Sanger: Yeah.

Cease: Which provided the gas atmosphere for the reactor.

Sanger: What was that? Was that helium?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: In other words, you kept the pressure right inside the reactor, etc.?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: Recirculator or whatever. What was your actual job, doing that?

Cease: Just kind of sitting around taking readings, because it was fairly well automatic.

Sanger: So you just watched the gauges to make sure the pressure was moving?

Cease: Did a little housekeeping.

Sanger: How many guys would be doing that on a shift?

Cease: Two.

Sanger: That was called a D operator?

Cease: Uh-huh.

Sanger: Then what? How long did you do that?

Cease: Oh, I do not remember.

Sanger: That was at 100-B?

Cease: Yeah. Then you went to a B operator. Then finally, you would get promoted to an A operator and you would do some control room work.

Sanger: What do they call the operators in the control room? Just “control room operators,” or what?

Cease: Well, in those days they called them “pile operators.”

Sanger: Did you do that then later?

Cease: Oh, yeah.

Sanger: At B, or somewhere else?

Cease: At B. I worked at all of them, except C and F.

Sanger: What does a pile operator do? When you did that, what were your duties?

Cease: You operate the reactor. Controlling the rods, taking readings. Take a turn at the console.

Sanger: When you are at the console, what are you doing? Keeping the reaction at a certain level?

Cease: Right.

Sanger: Is that difficult?

Cease: No. You cannot go to sleep.

Sanger: How would you do that, in those days?

Cease: You got a galvanometer right in front of you. Any minor movement of a control rod would move it.

Sanger: What was that the measuring? The reactivity?

Cease: It was a chamber under the reactor.

Sanger: And it would tell you what was happening inside?

Cease: Yeah. If you sit there and look at it and it went to the left, you are losing power, you pull out a rod. If it went up—

Sanger: It went to the right.

Cease: Poke a little in.

Sanger: Did it require quite a bit of adjustments?

Cease: No, actually you get up and level out.

Sanger: Pretty stable?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: How many fellows would there be in the control room, usually?

Cease: Usually three in those days. It is different now, but in those days.

Sanger: Would they kind of shift off at the console?

Cease: Oh, yeah. Two on, two off, you just work around. You use one guy with relief while one went to lunch and this and that.

Sanger: But there was just one guy at the console at any time, [00:24:00] just one of those in each control room, right?And the other guys were reading gauges?

Cease: Yeah. We had a few thousand process tubes. The panellit that had to be read every day.

Sanger: That had every one of them on there? I have been in there. That is over on—here, this is the console.

Cease: If you walk in the control room, it is on your right. There are panels.

Sanger: It had a light for each one?

Cease: Oh, yeah.

Sanger: So if the light went out, that meant what? Or came on, which was it?

Cease: If it came on, there was something wrong.

Sanger: Did that happen very often?

Cease: Not really.

Sanger: Usually what would it mean if a light did come on?

Cease: It could be a malfunction of the gauge. Maybe it is an indication of a rupture, the tube is blocking up. Too blocked up, the pressure would go up.

Sanger: One of the slugs might break, do you mean?

Cease: Uh-huh.

Sanger: One of the fellows who ran that fish lab, Richard Foster, said that that happened once in a while, there would be a rupture. They would know about it down at the fish lab because they would be notified that they might watch for it. Then what would happen? You would pull, shut the whole thing down, or just pull that one tube?

Cease: You shut the whole thing down.

Sanger: And then replace it or check it?

Cease: Go up and try to push it and see if it pushed ok. If it did not, then you call in maintenance.

Sanger: They would have special tools to clear it?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: How long would it take you then to bring it back up?

Cease: Well, you usually are governed by downtime. If you had just started up and you had a rupture and went down, maybe your downtime would only be about eight or ten hours. But if you have been up operating for a while, maybe you would have twenty-four hours, or maybe thirty hours of downtime, before you could start it.

Sanger: Why is that?

Cease: The xenon build-up, poisons.

Sanger: Oh, so you had to wait for it to decay?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: Then you moved on to D?

Cease: Yeah, the next one.

Sanger: Were you in the control room then?

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: How were you trained to do that? Was it mostly on the job?

Cease: Oh yeah, training, there was no other place.

Sanger: What was your understanding of what you were doing there?

Cease: Did not have any.

Sanger: You did not know. What did you think you were doing?

Cease: Nothing. It did not bother me. I had a job, it was a war effort. That is the way it was. That is the way it was with everybody.

Sanger: I take it there was not a lot of speculation?

Cease: Ah, you used to talk about, “Well, maybe we are making Kleenex or clothespins.” You know, there was a lot of joshing.

Sanger: Joking, yeah. Obviously, you were in contact with people who did know what you were doing, but obviously, they never talked about it?

Cease: Oh no, never.

Sanger: Then when the bombs were announced, that was news to you?

Cease: Oh sure, to almost everybody.

Sanger: Do you remember what your feelings were about that, when it happened?

Cease: You know, I had that question—I talked to a fellow from Smithsonian, [Stanley] Goldberg. He asked me the same question. My feeling—my wife and I and another couple were walking down what they called the Congress Street Hill in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on a Sunday, going to the movies.

Sanger: When the bombs were dropped?

Cease: No, when we heard about—

Sanger: Hiroshima?

Cease: No, when we heard about the war being declared.

Sanger: Oh, I see.

Cease: And it had more effect on me then. It was just one of those things, you just took it in your stride. As far as the bomb—of course, at that time, at that moment, nobody knew what we had been doing [00:30:00] had anything to do with the bomb.

Sanger: When did that come out? A couple days? I have read the news releases. It was shortly after that.

Cease: It was not too long. They took the credit for it.

Sanger: You were obviously here when that happened.

Cease: Oh, yeah, yeah.

Sanger: What did Goldberg talk to you about?

Cease: Oh, roughly the same. Of course, his work has a little different theme. He wants to set up kin of a museum. He told me that he was trying to get some of the old instrumentation to set up in the institution and then he wants some information. I do not know whether they put it on tape or video or something.

Sanger: You stayed out at the project until you retired? Always in reactors?

Cease: Yeah. I had a chance to transfer a couple times to 200, but I did not want any part of it. I had a chance to change from operations to maintenance, and I did not want any part of that. I had a chance to change into the instrument department, but I did not want that. I was happy with my operations.

Sanger: Where did you wind up, then?

Cease: N [Reactor].

Sanger: You retired how long ago?

Cease: Eleven years, the 25th of this month. ‘75, July 25.

Sanger: You were in the control room there?

Cease: No, I was not certified.

Sanger: What were you doing out there then?

Cease: I had charge of what they called the EMS program for the 105-Building and the-109 Building.

Sanger: What is that?

Cease: The 109?

Sanger: Yeah, what is 109?

Cease: The 109 is the power side, where all the generators are and so forth. Provide the cooling for the reactors.

Sanger: What is EMS?

Cease: Equipment Maintenance Standards. We had EMS’s from daily to five years, and these [00:36:00] were issued to the different crafts. Let me give you a good example. Are you familiar with N Area, any of the equipment?

Sanger: A little bit. I went out there once.

Cease: Each reactor has, we call them 4RXGs, [inaudible] with chambers under the reactor and they indicate power level or activity, reactivity. They had to be checked, the trips on them, every day. The form is issued to the instrument people and they have to go in to the equipment and one is bypassed at the time and they check the trip on it to make sure that it has not drifted and so forth. That is what the EMS is.

Sanger: So you worked there when it was just started when it was new? N?

Cease: No. I did not go there until they shut down the Ks. I spent fourteen years at K West and then they shut that down. Then I went over to K East, and it was not long after they shut that down and then I went over. I had quite a bit of fuzz.

Sanger: Where did you live during the war out here, in Richland? Did you get a house right away?

Cease: No, I lived in Hanford, in the construction camp.

Sanger: Oh, you did?

Cease: For about three months. My wife came out in April, and she lived in Pasco. I guess it was late summer of 1944 when we got a one-bedroom pre-fab.

Sanger: What was it like in the barracks?

Cease: Just like any Army barracks. Two men to a room. Too far from the number one mess hall. I worked shifts, and they had one mess hall, number five, that was set up for all hours. In other words, if you were working graveyard and you went in there and wanted breakfast, that is fine. If you were working swing shift and you went in there and you wanted dinner, why, you got dinner.

Sanger: How was the food?

Cease: Good.

Sanger: Was there much trouble with criminal activity or rowdiness that you remember?

Cease: I never ran into it, but we were warned before we [00:39:00] got there that you had to keep everything locked up and you are liable to lose your shoes or your alarm clock and this and that. I never had anything. It was pretty rough around the tavern, but I never went to the tavern. I could have made money by going to Pasco and buying that old black rum and selling it, but my reputation was worth more than a ten-dollar bill for a bottle of rum.

Sanger: A lot of people, I guess, made some money that way.

Cease: Oh, yeah.

Sanger: I have heard a lot of stories about that rum. Nobody could figure out why it existed, or why there was so much of it.

Cease: I think we had a ration card, if I remember, in those days. You could buy everything on your ration card.

Sanger: Somebody said if you bought a bottle of whiskey, then you had to buy a bottle of that rum too.

Cease: I think so.

Sanger: For some reason, like they were trying to get rid of it.

Cease: Yeah, I do not where it came from. I never bought any and I never drank any of it.

Sanger: I talked to a guy, a fellow named Bob [Robert E.] Bubenzer who was with DuPont with the patrol. He was a superintendent, I guess, who had come out here early to set it up, the fire department and the police and the patrol. He had lots of good stories about the police, mostly the Hanford camp.

Cease: One thing that was interesting to me—first, I told you when I came here I was on patrol. They had a ten day training school, one day on the range. First two or three days, we went to school. There must have been fifty, sixty people in that classroom. I was just talking to a fellow, I cannot remember—Thomas, Sergeant Thomas, a little cocky rascal. He announced one night before they dismissed us to, “Bring a pencil or pen tomorrow. We are going to fill out some security cards.”

About ten people showed up the next morning.

Sanger: Is that right?

Cease: It always amused me. These guys were just picked up all over the country and hired, and they just cannot stand the security check.

Sanger: What happened to them? They just took off?

Cease: Never saw them again. I suppose they got on the bus and terminated.

Sanger: I know that this guy, Bubenzer, said that one of their big jobs was running down people who were wanted someplace else [00:42:00] and they were out here because they were desperate for work, the people.

Cease: Somebody was telling—and I cannot remember who it was—but they were in the tavern at Hanford one time in the evening, and this great big black guy, he was bragging about what he had done, and that was the end of him. I do not know whether—these fellows surely had to be in civilian clothes?

Sanger: You mean the undercover [inaudible]? Yeah, apparently you never knew where they were.

Cease: And you never knew here in town, if you went to a gin mill or something, who was sitting next to you at the bar. Of course, bars have never been my problem, so I never had that trouble.

Sanger: Have you gone back to Bridgeport?

Cease: Oh no. No way.

Sanger: You do not regret leaving there?

Cease: No, or Pennsylvania either. I had an emergency trip in the last week in March. I had one brother that lives up in the old hometown. I went up and spent a couple days with him. then I have another brother who lives in New Jersey, with Kinney Shoes. I spent a few days with Phil and I left out of Newark. It is nice to visit, but no more.

Sanger: How long have you lived here?

Cease: This house? About twenty-eight years.

Sanger: This is not one of the originals, is it?

Cease: No, no.

Sanger: Too far out.

Cease: These were built in ‘49 and ‘50. Do you remember, just before you got to school, you had a stop sign? Bright Avenue? That used to be the boundary of the old town.

Sanger: Oh, it was. What is that school? Is that original or not?

Cease: No, it was built after.

Sanger: What about that building farther toward town, that kind of dark wooden shingle thing?

Cease: On the way coming Williams on your left?

Sanger: Yeah.

Cease: That was one of the originals.

Sanger: Was that a dorm?

Cease: No, it was a school. It was a grade school.

Sanger: Was it?

Cease: Sacagawea.

Sanger: Oh, it was.

Cease: Named after the little girl who went with Lewis and Clark. They built a new one out toward the north of town.

Sanger: One of the physicists I talked to said that his kids went to that school, Sacagawea.

Cease: I have a niece that came out here, her folks came from New York. She started first grade there. All [00:45:00] the schools are named after—we got Sacagawea, Chief Joe. They are either Indians or men of the cloth, except Carmichael Junior High. That was named after a fellow that had a big cherry orchard here in town.

Sanger: Is that right?

Cease: That is one of the pitches we give the schoolkids, when we take them on a tour.

Sanger: You do not remember, do you, a big accident at the chemical waste, at the separation area, in the tank storage area, during construction?

This one I am talking about, was a fairly major accident, I mean by most accounts. But there does not seem to be any particular official record of it. There were either anywhere from five to seven killed when a tank collapsed on some boilermakers, who were working—

Cease: Oh, that was during construction.

Sanger: Yeah, right.

Cease: Yeah. Well the only thing that I know—I have heard this story, I think the only thing I can do it relate to you—that when they start these tanks, they are set up on cribbing. It is a little hard for me to understand. But they were using a lot of chipping hammers. Nobody noticed that it was moving, maybe just one-thousandth of an inch, see. It finally fell off the cribbing.

Sanger: What is a chipping hammer?

Cease: Oh, it is what they chip wells. It is air with a little—some kind of blade like that, to chip wells.

Sanger: And they were supposedly—I do not know, but I asked somebody who knows firsthand—I guess they were putting the bottom on it, is that it?

Cease: Yeah. Then after you get so far up, you can forget about that, because your welding is all done and everything. That is one hundred years ago.

Sanger: Yeah, well Priest Sweeney was called out there. This guy I just told you about, [Rpbert] Bubenzer, the patrol guy, he was working then. He was the one who mentioned seven killed. The priest thought there said five. That has nothing to do with the A-Bomb. But I wanted to mention an accident. Apparently, that was the biggest one. There were a couple other fatalities, but nothing like that. It was a subcontractor, I guess. DuPont was not doing that job.

Cease: I do not know who the contractor was at that time. But in later years, they would be with Chicago, briefing people like that. That is their business. But it was interesting—these last few they built, you could see the hole that was dug.

Sanger: Yeah. I went out. I was here Sunday. I went out, drove out to the WPPSS [Washington Public Power Supply System] Plants. I have never been back to the other two. That was interesting, to see that. It looked kind of a ghost town.

Cease: Did you have anybody that could take you in?

Sanger: No, I did not have anybody to come along. I just went out to the gate and turned around. Are there still people on duty on that one that is in mothballs, to keep it maintained?

Cease: There was the last time I was out there. That has been oh, a year and a half years ago. They keep it in pretty good shape.

Sanger: Well, the other ones are not, probably.

Cease: Oh no, they have given up the certificate on that.

Sanger: That is the one that is just number four.

Cease: No top on the dome or anything. But that number one was in good shape. It was clean. There were not any cobwebs around. They had ventilation in there. They maintained the humidity and all, and heat in the winter. It was excellent.

Sanger: Now the one that is in mothballs, is there any reactor equipment in there?

Cease: I do not think so.

Sanger: So basically, it is the building?

Cease: Just the dome and everything in it, yeah.

Sanger: That is a strange thing.

Cease: I do not know what the status of—have you been out to Satsop number three?

Sanger: Well, I was there once when I was with a paper the day that they announced that they would stop construction on them. That is the only time I was ever there. One of those is in mothballs and one has been cancelled, right? It is like here.

Cease: Yeah. Five, as I understand it, is cancelled and number three is mothballed.

Sanger: Because I know that one of them—that must have been three—was really a long way along.

Cease: I think it is about the same status as this one out here, sixty, sixty-five percent, something like that.

Sanger: They have those massive cooling towers, tall cooling towers out there, which are pretty impressive.

[Louise’s interview]

Sanger: Because I know that a couple of the women have said–they were usually happy with the houses and furniture, and the rent was cheap.

Louise Cease: Those are my opinions. When we first came here, it was kind of wild.

Sanger: In what way?

Louise Cease: Well, there was nothing here. And when we came, the sand was knee-deep.

Sanger: Oh, it was?

Louise Cease: Oh, yeah.

Sanger: Was that because it was blowing, all the cover was gone, or what?

Louise Cease: There was not anything here. When we picked out our first house, it was a one bedroom pre-fab. Of course, there was a dirt road from Pasco to Hanford. We rode the bus out from Pasco and came up, and I guess it was—

Cease: Lee.

Louise Cease: Lee, well, it is Lee now. And then we would cut across a big sand dune, which is now the – is it the high school?

Cease: Carmichael.

Louise Cease: Carmichael High – Carmichael Junior High now. That was just a big sand dune. We walked up that, and came down to what is now Potter, and picked out our one-bedroom pre-fab. At the time, it was only half built. The plumbing was in and stuff like that. We were the only one on that street that had two plum trees in the yard. That was really something.

Sanger: Why did you have two plum trees?

Louise Cease: Because they left them there.

Sanger: Oh, was it an orchard?

Louise Cease: Yeah. There was no air conditioning then. It was hot.

Cease: No grass.

Louise Cease: No grass, but the city gave us the grass.

Sanger: Oh, the grass seed?

Louise Cease: Yeah, the grass seed. But before that, we had bulldozers running back and forth in front and back of the pre-fab, leveling the ground and stuff. Then we had the grass seed to put in. We had the best lawn in the neighborhood.

Sanger: Oh, you did?

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: Was there plenty of water?

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Cease: Oh, yeah.

Louise Cease: Lots of irrigation. See, there used to be an irrigation canal run down through the town. In fact, it came down back over here and then it went clear down to the – oh, where did it go?

Cease: Oh, right behind—

Louise Cease: Right behind Potter, between Potter and Sanford.

Cease: Yeah, and then it swung in behind the Carmichael and went on down, and crossed over there at the top of the hill.

Louise Cease: So we got our water from the irrigation ditch, of water.

Sanger: So you had a one bedroom pre-fab? Was that a single house?

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: They could build those in what, a day or so?

Cease: They were built on the coast someplace and hauled all over – Portland, I think. I do not know where.

Sanger: What was it like?

Louise Cease: You walked in. It had a little porch out front. You walked in the front door. To the left was a combination living room and dining area. Then to the right was the kitchen, a little kitchen. Then off the kitchen was a bedroom. Off the kitchen also was the bathroom, only it just had a shower, no bath.

Sanger: No bath?

Louise Cease: No bath, just a shower.

Sanger: Was it furnished?

Cease: Yeah.

Louise Cease: Yeah, it was furnished. One time we went to Spokane on the bus – or the train, I guess then. We came home. It had leaked right in the center of the bed. So the whole bed was soaking wet.

Sanger: The roof leaked?

Louise Cease: Yeah. Then in those days, we had these terrible sandstorms. I was working at Penney’s in Pasco. So I took the dumb bus everywhere. That bridge, the old bridge, was real narrow. He had passed a hay truck or something. Of course, we also had the windows open. It was so close the hay had come in the windows.

He worked in the area and he worked shift work. He would go to bed in the morning, and leave the windows and everything open. At night, when he got up, you could see his imprint in the bed.

Sanger: From the sand?

Cease: Yeah.

Louise Cease: The sand, yeah. Oh, we had an awful lot of sand.

Sanger: That was mostly because there was not any vegetation?

Cease: Right.

Louise Cease: Yeah, it was just all sand.

Sanger: Was that the biggest problem?

Louise Cease: It was not really a problem, because it was easy to pick up. We came from the east. Back there, you had dirt, but you had greasy dirt. It would stick to everything. You would have to scrub it. But this, all you had to do was get the sweeper and sweep it up. We did not have any humidity. It was dry sand.

Sanger: You worked at Penney’s in Pasco?

Louise Cease: I worked at Penney’s in Pasco. I worked at Penney’s back east. Before I came out, Bill had gotten acquainted with a manager at Penney’s. He said if I came out, would I be given a job? He said sure. So he gave me a job. I worked in there for a while. Then when he [Bill] went on shift work and stuff, I quit, because we were writing each other notes, you know, and all that.

Cease: Well Mr. Coplin was so nice that we did not feel like we just wanted to leave him, because help was hard to get.

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Cease: I went in to see him. I said that my wife had worked in a Penney’s in the East. I said, “I wonder if she could have a job?”

“Well, how long has she worked?” He asked.

I said, “Oh, about four or five years.”

He said, “Put her on the next train.”

I said, “How about a place to live?”

He said, “We will find a place.” After she got here, got the job, got a place to live. He told me, he said, “I had no idea in the world where that girl was going to live. But I needed an employee.”

Louise Cease: He found me the cutest thing. The people’s name was Bauman. Their home is no longer there in Pasco. It is where the – what is there now, a restaurant?

Cease: Yeah.

Louise Cease: You go over the top of the old bridge. Across from there is a big motel, across the street now. But they were in the same circumstances we were. They had sand to grow stuff in. But they had the most beautiful garden. They raised cantaloupe and watermelon, everything.

I could not believe that they could grow that kind of stuff in sand. They told us that it was the chemicals in the sand that made everything grow so good. All they did was water. They did not fertilize and all that.

Cease: But she got a room with kitchen privileges for ten dollars a week. Boy, I am telling you, that was a steal in those days, because there just was not any room available.

Sanger: Because of the project?

Cease: Yeah.

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: What did you pay for the pre-fab? Do you remember?

Cease: $27.50.

Louise Cease: $27.50 a month.

Sanger: Now, that included what?

Cease: Everything.

Louise Cease: Everything. We had baseboard heat.

Cease: No, we had the heaters, electric heaters.

Louise Cease: Yeah, electric heaters.

Cease: That was your electricity, your water, sewer, the whole ball of wax. Furniture.

Sanger: How long did you stay there?

Cease: About one year.

Sanger: Are those all gone, those houses?

Cease: No, there are a lot of them.

Sanger: Are there?

Louise Cease: There are a lot of them over here.

Cease: That little house is still there.

Louise Cease: Yeah, Potter, Sanford. There are quite a few of them around. They have made them a little more substantial. In those days, it was normal. Once in a while when we would get a good wind, they would blow out the – some of them would blow off.

Cease: Sometimes, the roofs would blow off.

Louise Cease: Yeah, but they have improved them since then and put betters roofs on, better foundations, and stuff like that.

Sanger: They are still recognizable, though?

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: What was Pasco like in those days?

Louise Cease: Terrible. If he had not been there to meet me at the train, I would have gone on someplace, I do not know – California.

Sanger: What was it like? Was it a lot of rough people?

Louise Cease: The station was just – all the time, people were coming and going. Men, especially, came here to work maybe for three or four weeks, and they did not like it. They would go into the station and—

Cease: They would be lying all over the place.

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Cease: Of course, I am sure you have never been in a station or an airport where they had a comfortable seat.

Sanger: Yeah.

Cease: I never have.

Louise Cease: But yeah, but it was terrible. The men, they never shaved or anything. It was hard to get laundry and stuff done here, if you were around early, because they did not have laundromats and all that stuff in those days.

Sanger: It was pretty crowded, I suppose?

Louise Cease: Well, it was out in the barracks.

Cease: Tell him about how they used to come in. They would wear their clothes until they could not stand them any longer.

Louise Cease: Yeah, and then they would come in and buy a new pair.

Sanger: At Penney’s?

Cease: They had no other outfit.

Louise Cease: Overalls, they wore a lot of overalls. They would wear them until they could not wear them any longer. Then they would come in and buy a new one.

Sanger: Oh, they would not – no washing?

Cease: No.

Louise Cease: Oh, no, no, unless somebody – some of the people on in the trailer parks had washers. We had one friend that made a fortune doing laundry for some of these guys that did not have any place to get it done.

Sanger: A lot of people, then, probably lived in trailer parks out off the project?

Louise Cease: A lot of them lived in barracks.

Sanger: With their families.

Louise Cease: They did not have any facilities to wash that stuff. So this one friend of ours, she came from South Dakota, and she had to bring her washer.

Cease: No, John went to the [inaudible] and bought an old beat-up secondhand Maytag.

Sanger: She went into the laundry business?

Cease: And she wound up with so much business, that she had to schedule people.

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: Where was she living?

Cease: In the trailer—

Louise Cease: In the trailer park.

Cease: Trailer park in Hanford.

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: At the camp?

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: I guess you could make some money at that.

Cease: Oh, yeah.

Louise Cease: Yeah, yeah, sure.

Cease: John was supervisor in transportation. They had one girl. They would take all their expenses, and lived off that washing machine.

Sanger: Oh, they did?

Cease: Yeah, and put John’s check in the bank every week.

Louise Cease:But then we moved to the B House.

Sanger: Was that a duplex?

Louise Cease: That was a duplex all on one floor. And boy, that was like moving into a castle by that time

Cease: That was heaven.

Louise Cease: Yeah. Although we had a lot of fun in that one bedroom pre-fab. He worked shift work.

Of course, everybody was from all over the country, and did not know anybody. So you go acquainted real easy in your neighborhood. All the neighbors would come in for breakfast when he would home from graveyard. They did not come in at night, on swing shift. But he would come home from swing, and we would have dessert. We really had to make our own friends and our own entertainment. There was not really entertainment or anything here then. So we played cards, and stuff like that. They did have out in the area, they had a big dance hall. They used to bring in name bands.

Sanger: Did you go to dances out there?

Louise Cease: Yeah. It was fun. But that is about all there was to do. We went to dances in Kennewick in the Grange Hall, I think it was. They had these old potbellied stoves. That was when the Navy was in Pasco. All the Navy guys used to come over to Kennewick and go to those dances. So outside of that, why, I am not sure where to drink it up, you know, in a bar or something, which was not our bag.

Sanger: Yeah, I suppose you made a lot of friends then?

Louise Cease: Oh yeah, yeah. We would make friends from South Dakota, North Dakota, Denver, and just all over. Then the south part of town, they called it “Little Denver.”

Sanger: Oh, they did?

Louise Cease: Yeah, because when the Denver people came, they had built a lot of houses in the south end. That is where they all located.

Sanger: Why did so many people come from Denver?

Louise Cease: Well, there was a plant there. He [Bill] could tell you, probably. I think it was a DuPont plant and they transferred a lot of the people from Denver, those that wanted to come.

Sanger: Would that have been before the war was over?

Louise Cease: I do not know if that – I believe it was. Those people that came from Denver, Bill, were there a DuPont plant there?

Cease: Yeah.

Louise Cease: And was that before the war?

Cease: It was an arms plant.

Louise Cease: Was that before the war, they all came? I was telling him about Little Denver, the south end of town. So then a lot of them transferred out here with DuPont. Then they started building all these private homes after that. They had a whole bunch of homes over there on the river. That was the Corps of Engineers. They had built houses for them. They were all over on the river, on the northeast side of town here. But they have all been torn down now.

Sanger: Oh, they have?

Louise Cease: Yeah, yeah, they were all torn down. Then private homes— well, they were out in there about where the school is now. It is connected with the university. So they were all out in that kind of northeast part of town. They were nice little houses, too. Then they had a club out there.

Sanger: Was that the Corps of Engineers Club?

Louise Cease: Yeah. I was telling them about those houses that were all torn down.

Cease: That was north Richland.

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Cease: Yeah.

Cease: The Corps of Engineers Club is right over here a couple of blocks.

Sanger: Oh, it is?

Cease: It was.

Sanger: The original?

Cease: Yeah, it was. It is gone.

Sanger: Oh, it is gone.

Cease: It was an old tract house that had been converted.

Sanger: Yeah, that is what he said. We have talked to [Col. Franklin T.] Matthias, and he talked about that place.

Louise Cease: Yeah, yeah. He was quite a gentleman, Matthias.

Then we rode horseback for a while for fun. In the process of that, we owned five different horses.

Sanger: You did?

Louise Cease: Yeah, and I had a horse and I had a colt. Then they had a rider’s club down here, where the barn is now. We used to go on chuck wagon rides along the Yakima River. Build a fire and have steaks, beans, and stuff like that.

Sanger: When was that? That period?

Cease: It was in the ‘40s.

Louise Cease: ‘40s, yeah. Late ‘40s, early ‘50s. That was kind of fun.

Sanger: You had been here since ’44? When did you move to Richland to the pre-fab, about mid- ’44?

Cease: Yeah.

Louise Cease: Yeah, right around the spring.

Cease: No, you landed in ’44.

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Cease: April.

Louise Cease: Yeah, yeah.

Cease: I think we got the house in July or August, something like that.

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Sanger: What, you are what, seventy—?

Louise Cease: Seventy-two. I was seventy-two in March. I am going on seventy-three.

Sanger: You met in Pennsylvania or in Bridgeport?

Louise Cease: Oh, no, in Pennsylvania.

Cease: Pennsylvania.

Louise Cease: Yeah, and in 1930—

Cease: Four.

Louise Cease: Four, and were married in ’38.

Cease: ’38.

Louise Cease: So we will soon be married – if we make it two more years, we will be married fifty years.

Sanger: Well, you were saying what happened to you in the Army?

Cease: Oh, I went up and a neighbor of mine, Harry Winslow, was the captain on the patrol. We went up together, and we passed. Before we were called, if I remember correctly, they passed a twenty-nine-year-old law. And that was it.

Louise Cease: And you were too old. And Harry went. I think he went [inaudible].

Cease: I do not know where Harry came from. I do not remember.

Louise Cease: But they took Harry and said Bill, no.

Sanger: That was in ’44?

Louise Cease: He was real disappointed he did not get to go.

Cease: But the family, they donated enough for the service.

Louise Cease: Yeah, his family. He lost a brother in the war.

Cease: Another one spent time in Korea. And the other one spent three and a half years in the South Pacific.

Sanger: Where did you lose your brother?

Cease: Java Sea.

Louise Cease: Java Sea.

Cease: Navigator on [B-]17, real early.

Sanger: Yeah, that would have been early, wouldn’t it.

Cease: January.

Louise Cease: We do not like sharing that.

Cease: ’42.

Sanger: That must have been one of the first B-17’s.

Cease: That was the problem.

Louise Cease: Yeah.

Cease: No tail gunner, and the Zeroes were knocking them out of the sky.